One of the saddest chapters in US history. Minidoka War Relocation Center was one of the “internment camps” constructed to house Japanese (many of whom US citizens) during World War II. Signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Executive Order 9066 ordered that all persons of Japanese Ancestry “excluded” from the West Coast of the United States. The order was specific to the West Coast, as Japanese in other areas (in particular Hawaii) did not face the same restrictions.

Minidoka War Relocation Center

Minidoka was 1 of 10 Japanese relocation centers that were built in the United States. Over 120,000 persons of Japanese origin were forced to abandon their homes and lives and be interred in one of thee camps across the country. Operated between 1942 and 1945, Minidoka housed nearly 13,000 persons over its time.

Built in Jerome County at Hunt, Idaho, and while named Minidoka the site locally became known as “Hunt Camp”. The site stretched some 33,000 acres with over 900 acres of housing blocks. Most of these buildings were demolished, but there still remain some for visitors to view.

When the first detainees arrived, the camp was still under construction. Many of the important areas such as housing and plumbing were rushed or only crudely constructed due to arriving prisoners. Many prisoners were forced to help built their own prison. Prisoners arrived by trains with the blinds closed so they would not know where they were going. Minidoka saw prisoners from Washington, Oregon, and Alaska.

Life at the Camp

Life at the camp was harsh. Southern Idaho in the High Desert had intense summers and winters and overall difficult weather. And the camp, crudely and hurriedly constructed but not for the climate.

They divided the camp into 36 residential blocks. Each block had 12 barracks, a mess hall, and a latrine. Each barrack had 6 units that would house either 1 family or several individuals. The dividers were not complete, and had no insulation and poor heating. It was a terrible place to live.

The Latrines were a simple row of toilets and rows of showers with no partitions. There was a general lack of privacy.

Overall it was a harsh existence, in particular for detainees arriving from the Pacific Northwest. Many did not have proper clothes for the environment.

People of the camps did the best they could. Many split up tasks, various different businesses would spring up to provide haircuts and other services. Children and folks set up sports teams. Children were born and others died. They tried to make the most of the life they had here.

Visiting the Camp

Minidoka is the second Internment Camp I visited after Manzanar, which was also the first camp constructed. Unlike Manzanar, where most of the buildings were destroyed, some buildings still remain at Minidoka.

It is a very emotional experience. I recall many years ago visiting Manzanar and being the only person not of Japanese descent there that day. Many of the folks I was visiting with were former prisoners or descendant of family members who were.

There are several trails through the camp that you can wander and seeing the guard booths and other areas start to really hit you about the prison.

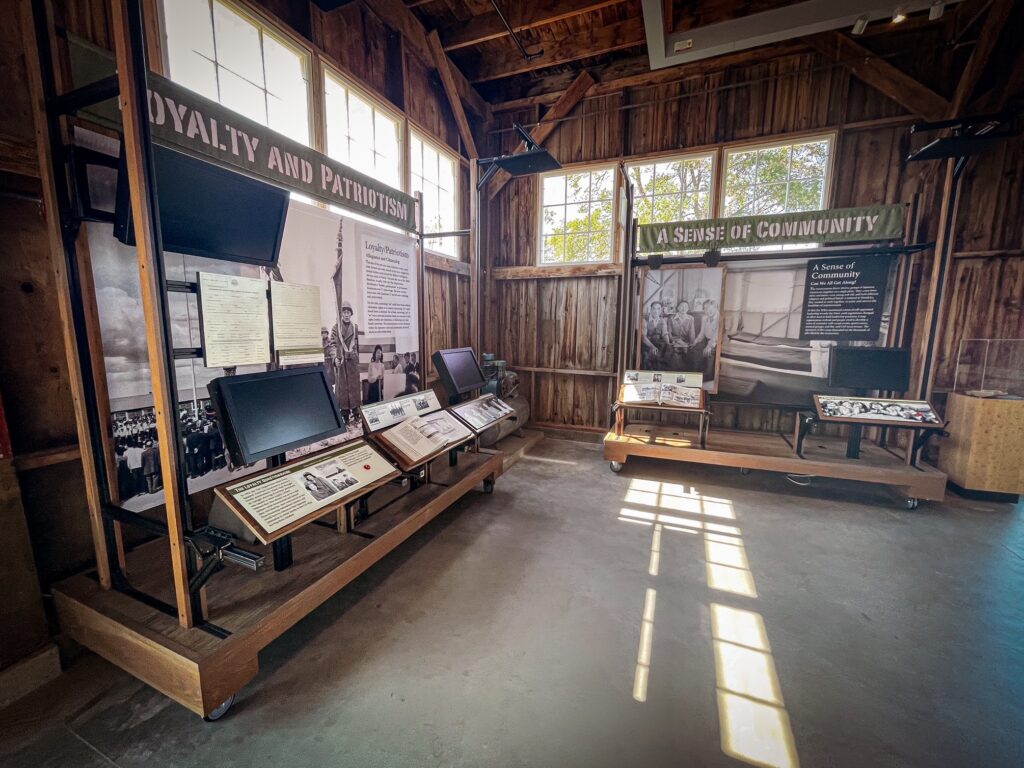

To me, the thing that really struck was the exhibits in the Visitor Center and the movie. Wandering and reading the history and the story of the people who were interred there is very emotionally moving.

The video especially, I was considering only watching a bit of it, but I couldn’t walk away. The movie, narrated by George Takei, runs about 30 minutes and is worth watching. It also covers some other tragic more recent things in prejudice and fear of others from modern day.

It think it’s hard to comprehend, especially the fact that many of the people were citizens and that didn’t protect them even.

Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial

The first exclusion area that was designated was Bainbridge Island of the coast of Washington State. On March 30, 1942, residents of Japanese ancestry were forced to gather at the ferry dock and sent to the concentration camp in Manzanar before being transferred to Minidoka.

NPS administers Bainbridge Island Memorial as part of the Minidoka National Historic Site. I was not able to visit this myself yet, but hope to on my next trip to Washington.

Basic Information

Address

Hours

10:00am – 5:00 pm – Open from May 27 – September 4th.

The Visitor Center closes during the winter. However the trails and grounds do remain open weather permitting.

Visitor Center

Address: 1428 Hunt Rd Jerome, ID 83338

The visitor center hours various exhibits that trace the history of the site and the exclusion order. There is also a movie that plays on the 1/2 hour. Definitely take the opportunity to watch the movie if you can.

National Park Passport Stamp

Minidoka Passport Stamp is available at the Visitor Center Above

Bainbridge Island Passport Stamp: There is also a passport stamp for Minidoka for Bainbridge Island. This is located at the Bainbridge Historical Museum (215 Ericksen Ave NE, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110)

Website: Official NPS Site

Getting There

Minidoka National Historic Site

Minidoka National Historic Site is located in Southern Idaho and administered by the National Park Service. Getting here:

From West:

Take I-84E to exit 165. Follow ID-25E for about 18 miles towards Jerome. Turn on Hunt Road (You should see signs for Minidoka)

From East:

Take I-84W to exit 188 for Valley Rd towards Eden. Take ID-25W to S Eden Road for about 11 miles and turn left on Hunt Road

Bainbridge Island

Bainbridge Island Memorial is located on Bainbridge Island at Pritchard Park – 4192 Eagle Harbor Drive, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110. To reach here you need to take the ferry from Seattle to Bainbridge Island.

Check Ferry Schedules here. Once on the Island you can get to the site via several ways by driving or public transportation. The Official NPS site has good info on getting there.

Leave a Reply